Essence of Playce

GENAI & I

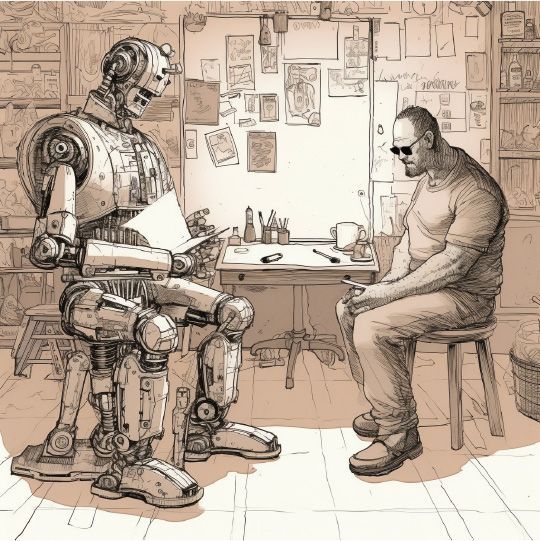

This is a collaboration. It’s about me meeting and working with a new creative partner. In the past I've mainly worked with other humans. But this partnership will be new. It will pair an organic intelligence with a synthetic one.

As in any partnership (be it romantic, creative or professional) the way our thinking differs is as important as how it converges. Artists learn through exposure to other art – the more the better. By looking, analysing, and deconstructing the intentions and solutions of others, we build a vocabulary rich enough to synthesise new solutions and use proven methods to solve new problems.

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GENAI) has been trained the same way; by exposure to the internet and the art it contains. The difference is that GENAI has been a much more attentive student than me. It can call upon a library of precedent that I can never match. Even after decades of looking at paintings and sculpture and art of all kinds, what I bring to the party is pathetically miniscule compared to the riches GENAI has collected and can remember in minute detail.

But I have one thing the GENAI doesn’t have (at least not yet). And that’s the need to create. AI can generate an endless variety of styles and artifacts. It's been designed to imitate them all. But It's motivation to do so is subtly, or maybe fundamentally different. Bhuddists believe that all pain derives from desire, and virtue and reward come to those who can overcome it. If so, GENAI has achieved a certain kind of Nirvana – free from desire.

But for the organic artist, often this 'need' is the driving force: the mental discomfort arising from an absence: the sense that, where there should be something, there isn’t. This is not always a pleasant sensation. Awareness of absence brings anxiety. Failing to fill it means that gap remains empty. And the effort required to find the precise-shaped peg to fit that hole can become all-consuming, with no guarantee it will ever be found.

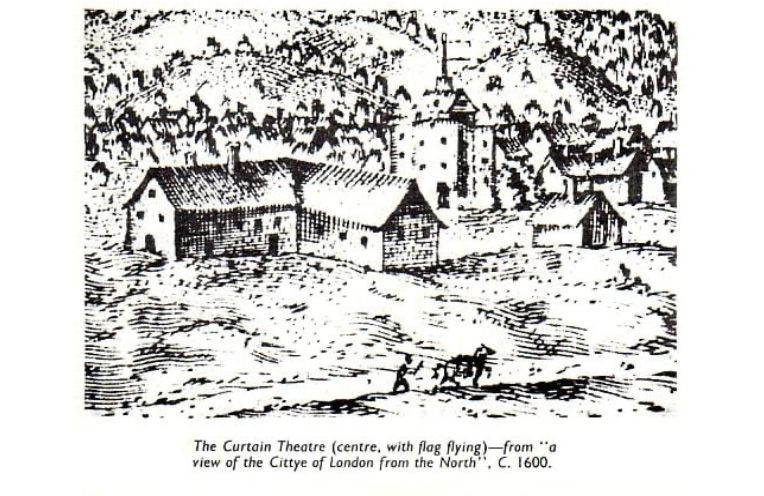

The Curtain Theatre

Absence is not just a mental condition. It can be physical.

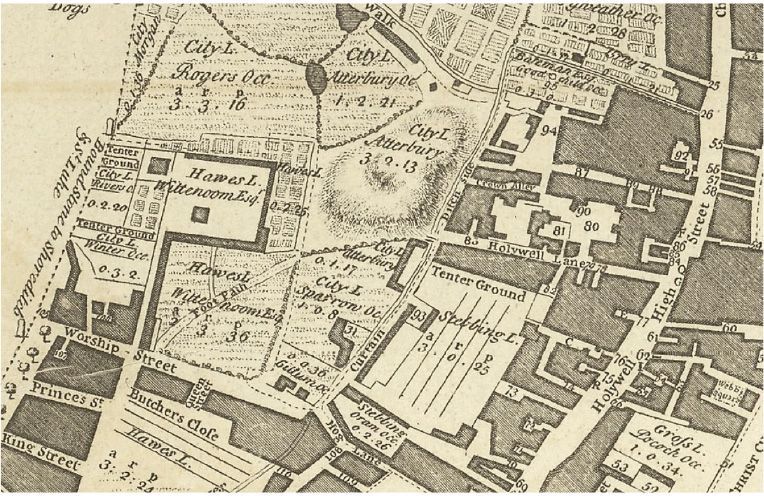

One day, a few years ago, I walked past a sign on a wall. Grubby and easily missed, it explained that 400 years before, this was the site of the Curtain theatre, where The Chamberlain's Men (of which one William Shakespeare was a member) had performed. Closed and probably demolished in 1630, it had been buried under successive waves of buildings for four centuries.

The foundations were discovered in 2015 while digging a hole to plant a

new tower block. Imagine the developer's dismay as work stopped for a couple of years, while the archaeologists slowly scraped away the accumulated mud and dirt and uncovered the stage where Elizabethan drama began.

Walking to work

At the time, I was working for a design agency in Spitalfields. A stone's throw from Bishopsgate, which I walked up and down several times a day.

I would think of how, 400 or so years earlier, William Shakespeare would have walked this exact same path from his lodgings in the parish of St Helens by Bishopsgate to work at the Curtain Theatre.

In those days, this meant leaving the jurisdiction of the City and entering a rougher neighbourhood. Being ‘without’ the walls meant that noisier fun like animal baiting, duelling and theatrical performances could proceed relatively unhindered by the authorities. London’s civic leaders didn’t share the popular enthusiasm for the rough entertainment the theatres provided to playgoers. Shapiro references an attempt by the privy council in 1597 to close the theatres, since they were:

‘...containing nothing but profane fables, lascivious matters, cozening devices, and scurrilous behaviours’ … vagrant persons, masterless men, thieves, horse stealers, whore-mongerers, cozeners, coney-catchers, contrivers of treason, and other idle and dangerous persons’.

Little has changed.

Shakespeare walking to work, from his lodgings in the city to the Curtain

Bishopsgate today

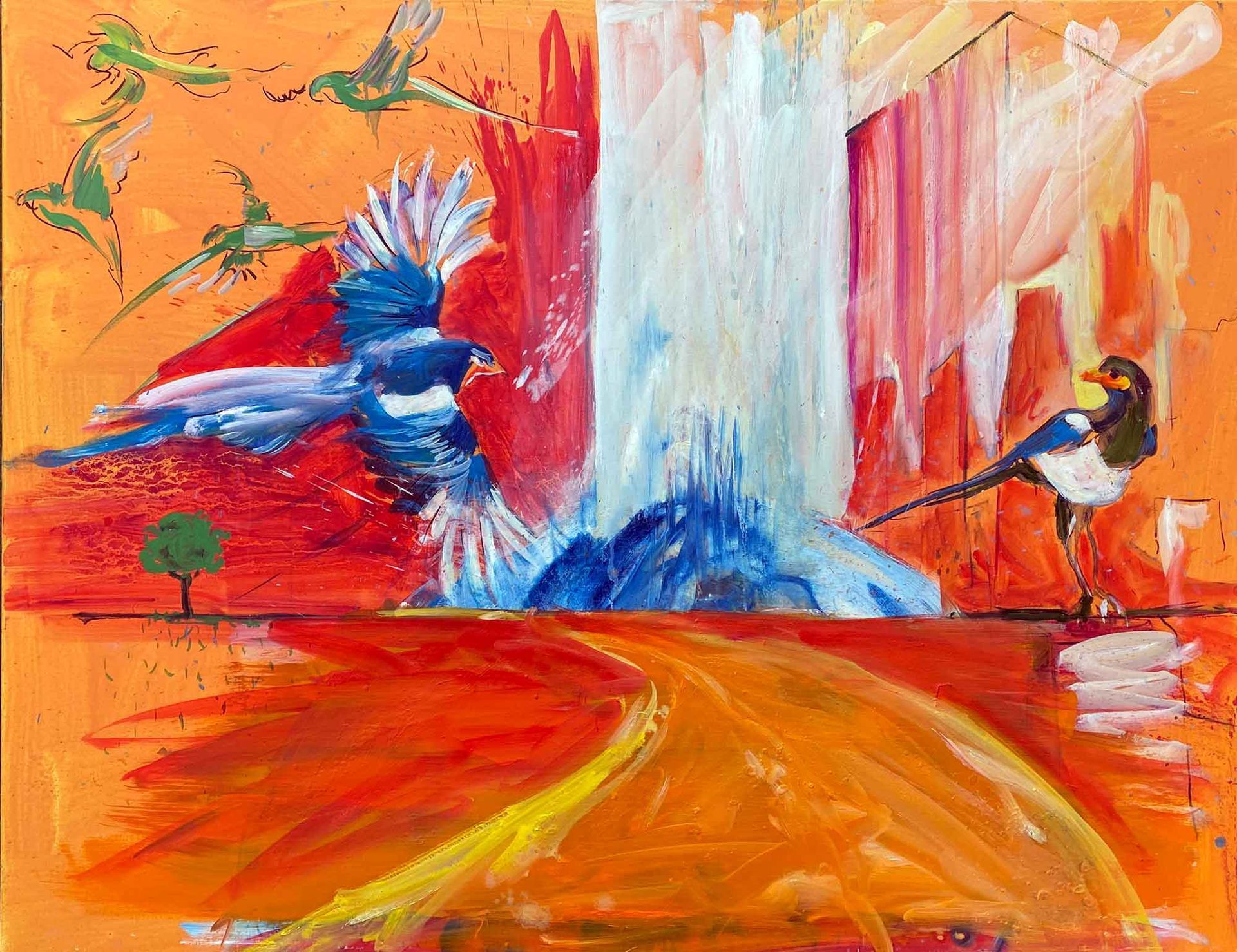

Painting

I began to dwell on this idea; of time being onion-skinned, and our twin commutes, his and mine, being somehow entangled; overlapping and simultaneous. And I wondered whether he might have, from time to time, sensed the imminence of the towers of glass and steel to come. Just as I would occasionally catch a glimpse of the buried world lying dormant beneath the concrete and of the modern era.

From 2018 until 2020 I worked on a number of large canvases exploring this idea. But they weren’t very good. I felt I’d seen them before.

I lacked the vocabulary necessary. Pigment suspended in oil is one of the most versatile materials – it can do anything you want, if you have the technical ability. But my mark-making seemed splap-dash and repetitive. The outputs had some vibrant charm but they didn’t really

look like

the idea I had in my head.

Painting is difficult. It involves reconciling an ideal image with a slowly developing actual one. To complicate matters, that ideal image may not yet exist. ‘I’ll recognise it when I see it' uses an ongoing dialogue between the sweep of a brush, the splash of liquid, the smear of a rag; by choice of hue, tint, medium; by the cohesion of the support, or the interaction of pigment that dries at different speeds and settles subject to density and liquidity – and a separate, critical position attuned to recognising and retaining the sensations to be recreated in physical form.

When mental image meets material manifestation it can summon magic or mess. Both as likely.

With these paintings I came face to face with my own limitations as an artist. I’d found a big subject – Shakespeare Walking to Work could incorporate literary, autobiographical, psycho-geographic references, as well as all the devices and subtleties that the canon of painting can offer.

I grew more and more disheartened by the limitations of my vocabulary and the predictable and banal solutions my technical skills as an artist could muster.

It was as if Shakespeare was writing with the vocabulary of a five-year-old – sufficient to convey broad intent, but without the capacity for invention or surprise. I felt there was a crucial tool missing from the kit.

I asked DALLE-2 to take a look at one of my paintings. Within seconds, the Generative Artificial Intelligence agent had produced a string of novel images with a fluidity and dynamism that I was struggling to achieve.

It seemed to have an uncanny ability to understand the alchemy of paint and imitate it. And even more spookily, it began to introduce characters and narratives that seemed to emerge from its own sensibilities – not mine.

I began working with another GENAI app: Midjourney. This appears to offer greater control and nuance. But it also seems to have strong convictions of its own.

By combining these outputs with other applications, such as Photoshop's Generative Fill, together we began to generate paintings reflecting on the idea of Shakespeare walking to work along Bishopsgate. His head full of words.

What are these? They look like paintings, but they're not paintings. They don't smell or feel like paintings. Because they emerge fully realised out of the software, we have no physical relationship with each other. They lack the shared experience of materiality that paintings confer. The synthesis of labour, skill and judgement to bring into being a real, physical entity. So what are they?

I began to worry that I was taking too dominant a role in this partnership. AI is so good at re-creating photographic interpretations of the world, and can call upon such a diverse range of styles and influences, why was I forcing it down such a narrow path? The essence of successful creative partnership is the give-and-take. Am I taking too much and not listening enough? Am I 'Humansplaining' when I should be listening more?

AI can do anything. But it seems always ready to learn more. I loved its facility with paint; the fluid handling of drip and soak; the skill in retaining the intensity of colours without letting them pollute each other. And then I would remember that it isn't paint. Just pixels. And images are lies. Or, more accurately perhaps, hallucinations.

What should we work on together?

I suggested my idea about Shakespeare. How I imagined him walking to work in the morning from his rented lodgings inside the City wall, through the gate, then north along Bishopsgate towards his place of employment in dodgy Shoreditch. And how that mirrored my own walk along the same route to work more than 400 years later.

The task was to find a vehicle to explore that sensation of entanglement. The peculiar sense of significance. This observation deserved closer inspection, trivial as it seemed. To do that I would have to attempt what so many others in the past have tried – to inhabit his head by imagining oneself into it.

I suspect that what the harried actor, profit sharer and playwright in a competitive market was thinking about as he walked to work – was work. And his work was words. Even though I'm not especially interested in his plays themselves, I do like some of the words.